Crossover Trial Design: How Bioequivalence Studies Are Structured

When a drug company wants to sell a generic version of a brand-name medication, they don’t have to run another full clinical trial. Instead, they prove it works the same way using a crossover trial design. This method is the backbone of nearly 9 out of 10 bioequivalence studies approved by the FDA. But how does it actually work? And why is it so widely trusted - and sometimes so risky?

Why Crossover Designs Rule Bioequivalence Testing

Imagine you’re testing two versions of the same pill: the original brand and a generic copy. In a typical clinical trial, you’d split people into two groups - one gets the brand, the other gets the generic. But people vary wildly. One person might metabolize drugs faster than another due to age, weight, or liver function. That noise makes it hard to tell if the difference is real or just bad luck. The crossover design fixes this by having each person take both pills - just at different times. You become your own control. If your body absorbs the brand-name drug at 85% efficiency and the generic at 83%, you’ve got a clear, direct comparison. No guesswork. No confounding variables. Just clean, personal data. This isn’t just clever. It’s powerful. When between-person differences are twice as big as measurement errors, crossover studies need just one-sixth the number of participants to reach the same statistical confidence as a parallel-group trial. That means fewer people, less cost, and faster results. For a typical bioequivalence study, that’s cutting from 72 volunteers down to 12-24. And for companies developing generics, that’s millions in savings.The Standard 2×2 Crossover: AB/BA

The most common setup is called the 2×2 crossover. It’s simple: two periods, two sequences. - Group A gets the test drug (T) first, then the reference drug (R) - known as the AB sequence. - Group B gets the reference drug (R) first, then the test drug (T) - the BA sequence. Between the two doses, there’s a washout period. This isn’t just a break. It’s critical. The washout must last at least five half-lives of the drug. Why? Because if even a trace of the first drug remains in your system, it could skew the second measurement. That’s called a carryover effect - and it’s one of the biggest reasons studies fail. For example, if a drug’s half-life is 4 hours, the washout needs to be at least 20 hours. But for drugs like warfarin (half-life up to 42 hours), that’s over 7 days. That’s why some studies drag on for weeks. The FDA and EMA both require documentation that drug levels dropped below the lower limit of quantification before the second dose. No guesswork. No assumptions. Proof.When the Drug Gets Tricky: Replicate Designs

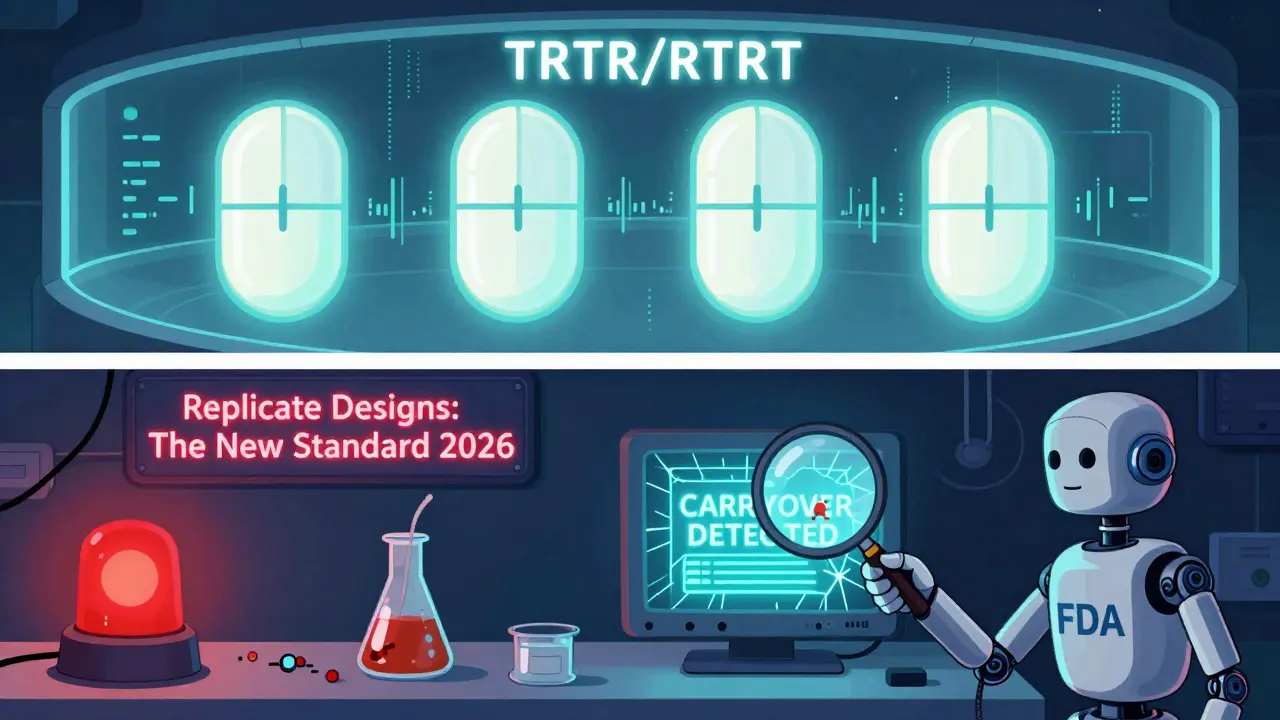

Not all drugs behave nicely. Some - like cyclosporine, prasugrel, or warfarin - are highly variable. That means the same person’s absorption can swing wildly from dose to dose. The intra-subject coefficient of variation (CV) might hit 40% or higher. In those cases, the standard 2×2 design loses power. The noise drowns out the signal. That’s where replicate designs come in. Instead of two doses, you get four. There are two main types:- Full replicate (TRTR/RTRT): Each drug is given twice. You get two doses of the test, two of the reference.

- Partial replicate (TRR/RTR): The reference is given twice, the test once. Simpler, but still gives you enough data to estimate within-subject variability.

Statistical Power and the 80-125% Rule

Bioequivalence isn’t about being identical. It’s about being close enough. The FDA and EMA agree: if the test drug’s exposure (measured by AUC and Cmax) is within 80% to 125% of the reference drug’s, it’s considered equivalent. That’s not arbitrary. It’s based on decades of clinical data showing that drugs within this range have the same safety and effectiveness profile. For highly variable drugs, the range widens to 75%-133.33%. But here’s the catch: you can’t just say “it’s within range.” You have to prove it statistically. The 90% confidence interval for the geometric mean ratio must fall entirely inside those bounds. If even one point sticks out - say, 126.1% - the study fails. Analysis uses linear mixed-effects models, usually in SAS with PROC MIXED. The model checks for three things:- Sequence effect: Did people who got the test first respond differently than those who got it second?

- Period effect: Did time itself change absorption? (e.g., seasonal changes, fasting habits)

- Treatment effect: Is there a real difference between the drugs?

Why So Many Studies Fail

You’d think this method is foolproof. But it’s not. According to FDA review data, 15% of major deficiencies in bioequivalence submissions come from poorly designed crossover trials. The most common mistake? Underestimating the washout period. A clinical trial manager once told me about a study that failed because they used a 7-day washout for a drug with a 10-day half-life. Residual drug was still in the bloodstream. The second dose readings were contaminated. They had to restart - at an extra $195,000 cost. Another issue? Missing data. If someone drops out after the first period, you lose their entire control. That’s why dropout rates must be kept below 10%. Even one missing person can throw off the analysis. And then there’s software. Phoenix WinNonlin makes it easy with built-in templates. But if you’re using R’s bear package, you need advanced coding skills. Many small CROs get tripped up here. The math is sound - but the execution isn’t.

What’s Changing in 2026

The rules are evolving. In 2023, the FDA started allowing 3-period replicate designs for narrow therapeutic index drugs - like levothyroxine or phenytoin - where even small differences can be dangerous. The EMA is expected to finalize its 2024 revision this year, making full replicate designs the new standard for all highly variable drugs. Adaptive designs are also on the rise. Instead of guessing sample size upfront, some studies now use a two-stage approach: run a small pilot, check the variability, then adjust the sample size. In 2022, 23% of FDA submissions included adaptive elements - up from just 8% in 2018. But the core hasn’t changed. Crossover designs still dominate. Over 89% of the 2,400 generic drug approvals in 2022-2023 used them. Why? Because they’re efficient, precise, and scientifically solid - when done right.When Crossover Doesn’t Work

There are limits. If a drug has a half-life longer than two weeks - like some osteoporosis treatments - a crossover design is impossible. You’d need to wait months between doses. That’s why parallel designs still exist. They’re slower and costlier, but sometimes they’re the only option. Also, crossover isn’t used for drugs with irreversible effects. If the drug permanently alters your body - say, a chemotherapy agent - you can’t ethically give it twice. Again, parallel designs win here. And for drugs that cause strong side effects - nausea, dizziness - the second dose might be contaminated by lingering symptoms. That’s why some companies test these drugs in parallel, even if it costs more.Final Take

Crossover trial design is the quiet engine behind generic drugs. It’s not flashy. It doesn’t make headlines. But without it, we wouldn’t have affordable medications for millions. It’s elegant in its simplicity: let each person be their own control. Let the data speak clearly. But it’s also fragile. One missed washout. One statistical error. One poorly trained analyst - and the whole study collapses. That’s why the best bioequivalence teams don’t just follow guidelines. They understand the math, respect the biology, and never cut corners. The future? More replicate designs. More adaptive methods. But the crossover will remain king - because when done right, it’s the most honest way to prove two pills are the same.What is the main advantage of a crossover design in bioequivalence studies?

The main advantage is that each participant serves as their own control, eliminating variability between individuals. This allows researchers to detect smaller differences between drugs with far fewer participants - often cutting sample sizes by up to 80% compared to parallel-group designs.

Why is the washout period so important in a crossover trial?

The washout period ensures that the first drug is completely cleared from the body before the second drug is given. If any residue remains, it can influence the results of the second period, leading to carryover effects that invalidate the study. Regulatory agencies require proof - not assumptions - that drug levels dropped below measurable limits.

What’s the difference between a 2×2 and a replicate crossover design?

A 2×2 crossover gives each participant one dose of each drug, in two periods. A replicate design gives each drug twice - either full (TRTR/RTRT) or partial (TRR/RTR). Replicate designs are used for highly variable drugs because they allow regulators to estimate within-subject variability and apply scaled bioequivalence limits.

How is bioequivalence determined statistically?

Bioequivalence is determined by calculating the 90% confidence interval for the ratio of geometric means of AUC and Cmax between the test and reference drugs. If the entire interval falls within 80.00%-125.00% (or 75.00%-133.33% for highly variable drugs), the drugs are considered bioequivalent.

Can crossover designs be used for all types of drugs?

No. They are unsuitable for drugs with very long half-lives (over 2 weeks), drugs with irreversible effects, or those causing persistent side effects that could carry over between periods. In those cases, parallel designs are required.

Sarah B

February 9, 2026 AT 00:38Tola Adedipe

February 10, 2026 AT 07:06Patrick Jarillon

February 11, 2026 AT 09:28Marcus Jackson

February 11, 2026 AT 11:40AMIT JINDAL

February 11, 2026 AT 14:42Lakisha Sarbah

February 12, 2026 AT 23:17Ariel Edmisten

February 14, 2026 AT 08:16Niel Amstrong Stein

February 14, 2026 AT 21:47Paula Sa

February 16, 2026 AT 08:26Mary Carroll Allen

February 17, 2026 AT 17:34Joey Gianvincenzi

February 18, 2026 AT 09:45Ritu Singh

February 19, 2026 AT 02:27Mark Harris

February 20, 2026 AT 14:38Savannah Edwards

February 21, 2026 AT 22:11Heather Burrows

February 23, 2026 AT 20:56