Effective Patent Life: Why Market Exclusivity in Pharmaceuticals Is Shorter Than You Think

Most people assume a drug patent lasts 20 years. That’s what the law says. But in reality, by the time a new medicine hits the shelf, companies often have just 10 to 13 years left before generics can enter the market. That’s not a glitch-it’s the system. And it’s why drug prices stay high for longer than most realize.

Why the 20-Year Clock Starts Too Early

The 20-year patent term begins the day the inventor files the application. That’s usually years-sometimes over a decade-before the drug even enters human trials. Imagine filing a patent for a new smartphone in 2010, but not launching it until 2020. You’d only have 10 years of exclusivity, not 20. That’s exactly what happens with most drugs.Drug development is slow. Preclinical testing, Phase I, II, and III clinical trials, and FDA review take an average of 7 to 10 years. By the time the FDA approves the drug, half the patent clock has already run out. For some biologics, it’s even longer-up to 11 years lost before the product even reaches patients.

The Hatch-Waxman Act: A Compromise That’s Been Strained

In 1984, Congress passed the Hatch-Waxman Act to balance two goals: reward innovation and let generics in faster. It gave drugmakers a way to make up for lost time with something called Patent Term Extension (PTE). The law allows up to five extra years of patent protection, but with a hard cap: no drug can have more than 14 years of market exclusivity after FDA approval.That 14-year limit was meant to be the ceiling. But here’s the catch: many drugs never even hit that mark. The average effective patent life after approval is just 13.35 years, according to Drug Patent Watch. For some, it’s closer to 8 or 9. The math doesn’t add up to 20 years of real monopoly time. It’s more like 10 to 13.

What Happens After the Patent Expires? Not What You Think

When a patent runs out, generics are supposed to flood in and drop prices by 80-90%. But that rarely happens overnight. Why? Because brand-name companies don’t just rely on one patent. They file dozens.Secondary patents-on things like new pill coatings, extended-release formulas, or combinations with other drugs-are now standard. A blockbuster drug might have 20 to 30 patents stacked on top of each other. These aren’t always about better medicine. Sometimes they’re just about delaying competition. The R Street Institute found that high-revenue drugs are 37% more likely to get these follow-up patents than lower-selling ones.

This is called “evergreening.” It’s legal, but it stretches the original intent of the patent system. A drug approved in 2010 might have its core patent expire in 2023, but a second patent on a new delivery method keeps generics out until 2027. Then a third patent on a pediatric formulation adds another six months. The result? A 17-year monopoly, even if the original patent only lasted 13 years after approval.

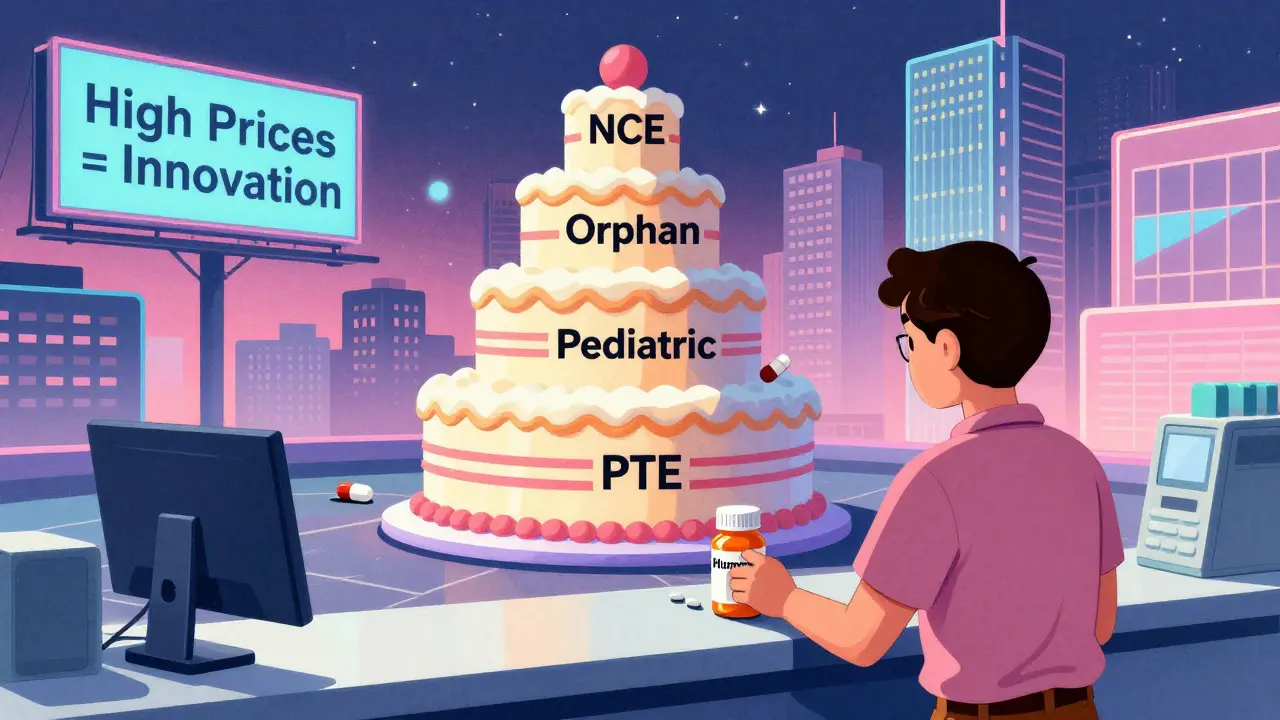

Regulatory Exclusivities: The Hidden Layers

Patents aren’t the only tool. The FDA also grants exclusivities that don’t depend on patents at all. These are separate protections:- New Chemical Entity (NCE): 5 years of exclusivity for a completely new active ingredient

- Orphan Drug Exclusivity: 7 years for drugs treating rare diseases (under 200,000 U.S. patients)

- New Clinical Investigation: 3 years for new uses or formulations of existing drugs

- Pediatric Exclusivity: 6-month extension added to existing patents or exclusivities

These can stack. A drug might get 5 years of NCE exclusivity, then 3 more years for a new formulation, plus 6 months for pediatric testing. Even if the patent expires, generics still can’t enter. That’s why some drugs stay exclusive for 15+ years without a single patent extension.

The 30-Month Stay: A Legal Delay Tactic

When a generic company files to sell a cheaper version, they must notify the brand-name maker. If the brand sues for patent infringement within 45 days, the FDA can’t approve the generic for 30 months-unless a court rules in favor of the generic sooner.This 30-month clock is often used strategically. Even if the patent is weak or likely to be invalidated, the lawsuit delays competition. Generic manufacturers face huge financial risk: if they launch before the court decides and lose, they owe millions in damages. So many wait. That gives the brand more time to sell at full price.

Global Differences: How Other Countries Handle It

The U.S. isn’t alone, but its system is unique. In Europe, the Supplementary Protection Certificate (SPC) gives up to 5 years of extension, similar to PTE. Canada’s Certificate of Supplementary Protection (CSP) offers up to 2 years. Japan allows up to 5 years of patent term extension too.But none of them have the same level of patent stacking and regulatory exclusivity as the U.S. That’s why drug prices in the U.S. are often double what they are in Canada or Germany. The system here is designed to protect profits more aggressively.

The Real Cost of Lost Exclusivity

When a drug loses exclusivity, revenue can drop 80-90% in the first year. For a blockbuster like Humira, which brought in over $20 billion annually, that’s a financial earthquake. That’s why companies spend millions on lifecycle management: tweaking the drug, finding new uses, or changing how it’s delivered just to reset the clock.It’s not just about science. It’s about business. The average cost to develop a new drug is now estimated at $2.6 billion (in 2013 dollars). That’s why companies fight so hard to squeeze every last month of exclusivity out of the system.

Is the System Broken?

The Hatch-Waxman Act was designed to be a fair trade: give innovators enough time to recoup costs, then let generics compete. But today, 91% of drugs that get patent extensions keep their monopolies going long after those extensions expire-thanks to secondary patents and exclusivities.That’s not what Congress intended. The system is working, but not as it was meant to. The result? Patients and insurers pay more for longer. And while innovation is still rewarded, the path to affordable medicines is getting longer, not shorter.

There’s no easy fix. But understanding how the clock really works helps explain why some drugs stay expensive for over a decade-even after their patents are “expired.”

Ian Long

January 7, 2026 AT 19:30Okay but let’s be real - if you’re spending $2.6 billion to make a drug and then only get 12 years to make it back, of course you’re gonna stretch every patent you can. It’s not evil, it’s capitalism. The system’s broken, but the companies aren’t the villains - the regulators are.

Matthew Maxwell

January 8, 2026 AT 11:04The notion that pharmaceutical companies are somehow 'abusing' the patent system is a myth perpetuated by those who don’t understand intellectual property law. The Hatch-Waxman Act was carefully crafted to incentivize innovation. To suggest otherwise reveals a fundamental misunderstanding of economic incentives and the cost of R&D.

Lindsey Wellmann

January 10, 2026 AT 00:10so like… imagine your phone’s patent expired after 10 years but the company kept selling it with a new case and called it ‘iPhone 2.0’?? 😱💸

also why is my insulin still $300?? 🤬 #pharmaisaripoff

Micheal Murdoch

January 10, 2026 AT 02:47This is one of those topics where the truth sits right in the middle. On one hand, yes - the system was designed to reward innovation, and without patents, no one would risk billions on unproven science. On the other hand, the stacking of secondary patents, regulatory loopholes, and 30-month stays have turned what was meant to be a temporary incentive into a decades-long monopoly. It’s not that companies are evil - they’re just responding to incentives. The real failure is in the lack of systemic reform. We need smarter rules, not just outrage. Maybe a cap on patent stacking? Or automatic generic entry after 12 years post-approval, regardless of secondary patents? We can honor innovation without letting it strangle affordability.

Jeffrey Hu

January 10, 2026 AT 19:01Everyone says ‘patents are only 10-13 years’ but they forget the FDA exclusivities. NCE = 5 years. Pediatric = +6 months. New formulation = +3 years. That’s already 8.5 years without a single patent. And that’s before evergreening. The 20-year myth is just that - a myth. The real issue is transparency. Nobody tells patients this stuff.

Drew Pearlman

January 11, 2026 AT 10:46I know this sounds harsh, but hear me out - if we didn’t have this system, we wouldn’t have life-saving drugs like Keytruda or Humira in the first place. Yes, prices are high, but think of all the people who are alive today because someone took that risk. Maybe we need price controls, but don’t punish the innovators. The real problem is insurance and middlemen, not the patents. Let’s fix the system, not the science.

Meghan Hammack

January 12, 2026 AT 12:34My dad died because he couldn’t afford his meds. I don’t care about patents or ROI. I care that people are dying so CEOs can buy private islands. This isn’t innovation - it’s exploitation.

RAJAT KD

January 14, 2026 AT 07:28US system is worst in the world. India and Brazil produce generics faster. Why? No patent stacking. No 30-month stays. Simple. Clean. Fair.

Darren McGuff

January 15, 2026 AT 04:57Interesting read. I work in EU pharma regulation, and the SPC system here is much tighter. We don’t allow patent stacking the way the US does. The result? Generics enter faster, prices drop quicker, and innovation still happens - just without the predatory tactics. The US could learn a lot from Europe’s balance.

Heather Wilson

January 16, 2026 AT 16:02Let’s not pretend this is about science. It’s about shareholder value. Every secondary patent is a calculated financial move, not a medical advancement. And the fact that 91% of extended patents still block generics after expiration? That’s not innovation - that’s fraud dressed up as IP law.

Chris Kauwe

January 17, 2026 AT 16:17America built the greatest pharmaceutical industry on the back of strong IP protections. To weaken it is to surrender global leadership. China and India may churn out generics, but they don’t invent breakthroughs. If you want cheaper drugs, stop importing innovation and start funding it yourself - or accept that free rides end when the plane runs out of fuel.

Alicia Hasö

January 17, 2026 AT 18:48There’s hope. Grassroots movements, state-level price caps, and new legislation like the Elijah Cummings Lower Drug Costs Now Act are pushing real change. We’re not powerless. Patients are organizing, lawmakers are listening, and the public is waking up. This isn’t the end - it’s the beginning of a fairer system. Keep speaking up. Your voice matters.