Hatch-Waxman Act: How It Shaped Generic Drug Access in the U.S.

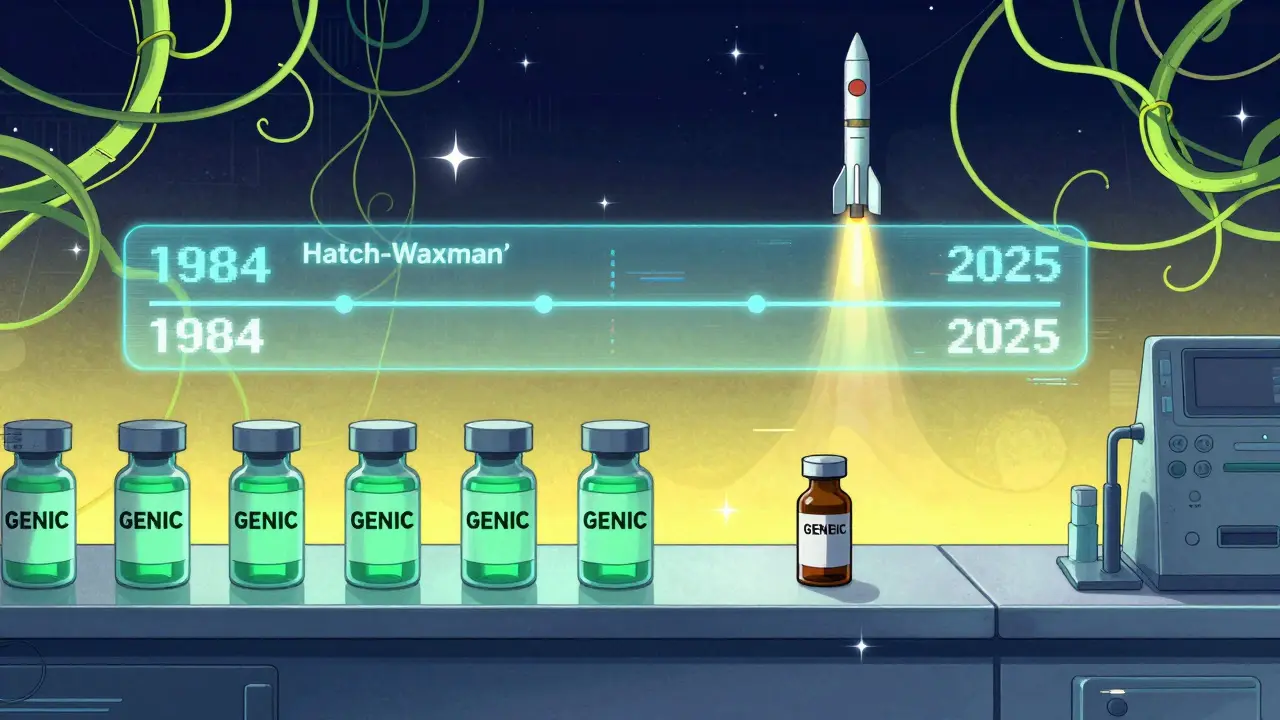

The Hatch-Waxman Act didn’t just change how drugs get approved in the U.S.-it rewrote the rules of the entire pharmaceutical market. Before 1984, generic drugs were rare. Fewer than 10 got FDA approval each year. Today, 9 out of 10 prescriptions filled are for generics. That shift didn’t happen by accident. It was engineered by a law passed on September 24, 1984, that brought together two powerful forces: brand-name drug companies and generic manufacturers. The goal? A fragile, but functional, balance between innovation and affordability.

What the Hatch-Waxman Act Actually Did

The full name of the law is the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984. It’s named after its two sponsors: Representative Henry Waxman and Senator Orrin Hatch. But the real story isn’t about politics-it’s about solving two urgent problems. First, brand-name drug makers were losing valuable patent time. The FDA approval process could take 7 to 10 years. By the time a new drug hit the market, half its patent life was already gone. That meant less time to recoup billions spent on research. Second, generic companies couldn’t even start testing their versions until after the patent expired. A 1984 Supreme Court case, Roche v. Bolar, ruled that doing so was patent infringement. That meant generics couldn’t get ready to launch until after the brand drug’s patent ended. Patients paid high prices longer. And manufacturers lost out on market entry. Hatch-Waxman fixed both problems at once. It gave innovators a way to extend their patents to make up for time lost in FDA review. At the same time, it created a legal shortcut for generics to enter the market faster.The ANDA Pathway: How Generics Got Their Foot in the Door

The key tool for generics is the Abbreviated New Drug Application, or ANDA. Before Hatch-Waxman, every drug-whether new or copied-had to go through the same full clinical trials. That meant spending $100 million or more and waiting a decade to prove safety and effectiveness. The ANDA changed that. Instead of repeating every study, generic makers only had to prove their version was bioequivalent to the brand-name drug. That means it releases the same amount of active ingredient into the bloodstream at the same rate. No need for new safety trials. No need to prove it works again. The result? Generic development costs dropped by about 75%. Approval times shrank from 10 years to under 3. The FDA estimates that since 1984, this single change saved U.S. consumers more than $1.18 trillion in drug spending between 1991 and 2011.The Safe Harbor: Why Generics Can Test Drugs Before Patents Expire

One of the most clever parts of Hatch-Waxman is Section 271(e)(1), known as the “safe harbor.” It says generic companies can legally make, use, or test a patented drug-even while the patent is still active-as long as the only purpose is to gather data for FDA approval. Before this, generics had to wait until the patent expired. Now, they can start testing up to five years early. That’s why you often see a generic drug launch the day after a patent ends. They’ve already been approved. They just waited for the clock to run out. This provision was the direct answer to the Roche v. Bolar ruling. It turned a legal barrier into a timed race. The first generic company to file an ANDA with a patent challenge gets a huge prize: 180 days of exclusive market access. No other generic can enter during that time. That’s why companies used to camp outside FDA offices in the 1990s-trying to be first in line.

Patent Term Restoration: The Trade-Off for Innovators

To get generics to agree to this system, brand-name companies needed something in return. Hatch-Waxman gave them a way to extend their patent life. The USPTO can restore up to five years of patent time lost during FDA review, but the total patent life can’t exceed 14 years from the drug’s approval date. On average, companies got about 2.6 years back. That’s not a huge extension-but it’s enough to make a difference. For a blockbuster drug that brings in $1 billion a year, an extra two years means $2 billion in revenue. But here’s where things got messy. Companies didn’t just rely on the original patent. They started filing dozens of secondary patents-on new dosages, delivery methods, or even minor chemical tweaks. By 2016, the average drug had 2.7 patents listed in the FDA’s Orange Book. In 1984, it was just 1.5. Today, some drugs have over 14 patents. These “patent thickets” became a way to delay generics. If a generic company challenges one patent, the brand company files another. The legal battles drag on for years. The FTC found that between 2010 and 2022, 262 drugs stayed on the market past their original patent expiration because of these tactics.How the System Got Gamed

The Hatch-Waxman framework worked beautifully-for a while. But over time, both sides found ways to exploit it. Brand companies began using “product hopping.” They’d make a tiny change to a drug-like switching from a pill to a capsule-and then launch the new version. They’d stop selling the old one. Patients were forced to switch. Generics couldn’t easily copy the new version if it was patented. This reset the clock. Then came “pay-for-delay.” Brand companies would pay generic makers to hold off on launching their cheaper version. Between 2005 and 2012, 10% of all patent challenges ended this way. The FTC called it anticompetitive. In 2013, the Supreme Court ruled these deals could be illegal-but they didn’t stop. They just got more creative. Generic companies, meanwhile, began gaming the 180-day exclusivity. Some would file ANDAs just to block competitors, then sit on them for years. Others would challenge patents they knew were weak, hoping to force a settlement. The system, meant to encourage competition, sometimes became a tool for delay.

Christina Widodo

January 12, 2026 AT 08:54So basically, Hatch-Waxman was the original win-win-until everyone started cheating? That’s wild. I never realized how much of our drug prices hinge on legal loopholes and timing games.

Alice Elanora Shepherd

January 13, 2026 AT 01:37It’s staggering how one law, written nearly 40 years ago, still dictates whether millions can afford their medication. The ANDA pathway was genius-until it wasn’t. Now, it’s a minefield of patent trolling and corporate maneuvering. We need to return to the spirit of the law, not the letter.

Faith Wright

January 13, 2026 AT 14:52Of course the pharma giants turned this into a monopoly machine. They always do. They’ll patent the color of the pill next. At this point, ‘innovation’ just means ‘how long can we delay the cheap version?’

Prachi Chauhan

January 15, 2026 AT 07:56Think about it: without this law, we’d be paying $500 for insulin like in the 90s. But now? Companies stretch patents like taffy. They don’t innovate-they litigate. And we pay. Again. And again. And again.

Audu ikhlas

January 17, 2026 AT 04:50USA invented this system and now we’re the only ones who pay 10x more than everyone else. Why? Because we let greedy CEOs run the show. Other countries negotiate prices. We let lawyers do it. Pathetic.

TiM Vince

January 18, 2026 AT 03:03It’s funny how the ‘safe harbor’ clause-meant to speed up generics-ended up turning drug approval into a sprint with legal landmines. The first mover gets 180 days of monopoly? That’s not competition. That’s a lottery with billion-dollar prizes.

Bryan Wolfe

January 19, 2026 AT 19:50I love how this law was built on compromise-innovators get time back, generics get a fast track. But somewhere along the way, the compromise got replaced by exploitation. We’re not fixing the system-we’re just adding more layers of lawyers. The FDA’s new guidance on Orange Book listings? That’s a start. Let’s push harder.

Jay Powers

January 20, 2026 AT 07:18Pay-for-delay deals are the worst. It’s like the brand company pays the generic to not do its job. And we’re the ones who get stuck with the bill. The CREATES Act is good, but it’s like putting a bandaid on a broken leg. We need structural reform, not tweaks.

Katherine Carlock

January 20, 2026 AT 16:24Just saw my prescription cost $4 with a generic. $200 without. That’s not a savings-it’s a lifeline. And yet, we let corporations play chess with people’s health. It’s not just unfair. It’s cruel.

Sona Chandra

January 21, 2026 AT 08:29BRAND COMPANIES ARE ROBBING US BLIND AND THE GOVERNMENT IS SITTING ON ITS HANDS. THEY’RE NOT INNOVATING-THEY’RE LAUNDERING PATENTS. WE NEED TO BURN THE ORANGE BOOK AND START OVER. THIS IS A NATIONAL EMERGENCY.

Rebekah Cobbson

January 22, 2026 AT 18:38Thanks for laying this out so clearly. I’ve been on a $1,200 monthly med for years. My generic just dropped to $12. I cried. But then I read about pay-for-delay and realized-this could’ve been $12 ten years ago. That’s the real tragedy. We’re not just paying more-we’re paying for lost time.