How to Understand Boxed Warning Label Changes Over Time

When a drug gets a boxed warning, it’s not just a footnote-it’s a red flag. These bold, bordered alerts appear at the top of prescription drug labels in the U.S., designed to grab the attention of doctors and pharmacists before they even read the rest of the instructions. They don’t just say "be careful." They say: "This drug can kill you if used wrong." And over the last 45 years, these warnings have changed-becoming more specific, more data-driven, and more complex. If you’re a healthcare provider, a patient, or even just someone trying to understand why your medication label keeps updating, knowing how to read these changes isn’t optional. It’s essential.

What Exactly Is a Boxed Warning?

A boxed warning, also called a black box warning, is the strongest safety alert the FDA can require for a prescription drug. It’s not a suggestion. It’s a legal requirement. The warning must appear in a prominent border-traditionally black, though digital formats now allow other colors-right after the drug’s indication and before any other safety information. The content is tightly regulated: it must describe serious or life-threatening risks, like death, hospitalization, or irreversible harm. These aren’t side effects you might shrug off. These are events that can end a life or require emergency care. The FDA started using boxed warnings in 1979. Back then, they were broad: "May cause serious liver damage." Today, you’ll see something like: "Risk of myocarditis is 0.84 cases per 1,000 patient-years, with onset typically within the first 4 weeks of treatment. Perform baseline and weekly cardiac monitoring during initiation." That’s not vague. That’s actionable.Why Do These Warnings Change?

Drug safety doesn’t stop at approval. The FDA doesn’t wait for a drug to be on the market for decades to act. It monitors real-world use through millions of reports from doctors, patients, and hospitals. Each year, the FDA receives about 1.2 million adverse event reports through its MedWatch system. When enough signals point to a new danger, the agency reviews the data and decides whether to update the label. Some changes happen because we learn more about who’s at risk. The antidepressant boxed warning, first issued in 2004, originally only mentioned children. By 2006, it was expanded to include young adults aged 18 to 24. Why? Because post-marketing data showed suicide risk wasn’t just a pediatric issue-it was also elevated in early adulthood. Other changes come from better science. In 2017, the warning for Unituxin (dinutuximab) replaced the term "neuropathy" with "neurotoxicity." It sounds like semantics, but it’s not. "Neuropathy" just means nerve damage. "Neurotoxicity" tells you the damage is caused by the drug itself, not by the disease. That distinction changes how doctors monitor patients and when they decide to stop treatment.How to Track Changes Over Time

You can’t rely on memory or old printouts. The FDA keeps a public, searchable database called Drug Safety-related Labeling Changes (SrLC), which includes all boxed warning updates since January 2016. It’s updated every quarter. For older changes, you’ll need to dig into the MedWatch archive or Drugs@FDA, which shows the full history of a drug’s label from approval onward. Here’s how to use it:- Go to the FDA’s SrLC database.

- Search by drug name or date range.

- Look for entries marked "Boxed Warning" under "Change Type."

- Compare the "Previous Text" and "Revised Text" columns side by side.

What the Changes Tell You About Risk

Not all boxed warnings are created equal. Some warn about rare but deadly risks. Others warn about common but manageable ones. The way the language has evolved tells you how confident the FDA is in the data. Early warnings (1980s-1990s) used phrases like "may cause" or "rare cases of." Today, you’ll see precise numbers: "1 in 500 patients," "2.3 times higher risk," "incidence of 0.84 per 1,000 patient-years." This shift means the FDA is now acting on real-world data, not just theoretical concerns. Also look for what’s added: specific populations, monitoring requirements, contraindications. The 2004 Depo-Provera warning didn’t just say "bone loss." It added: "The degree of loss appears to increase with duration of use and is partially reversible after stopping." That’s not just a warning-it’s a guide for how long to use the drug and what to do if you stop.When Warnings Don’t Work

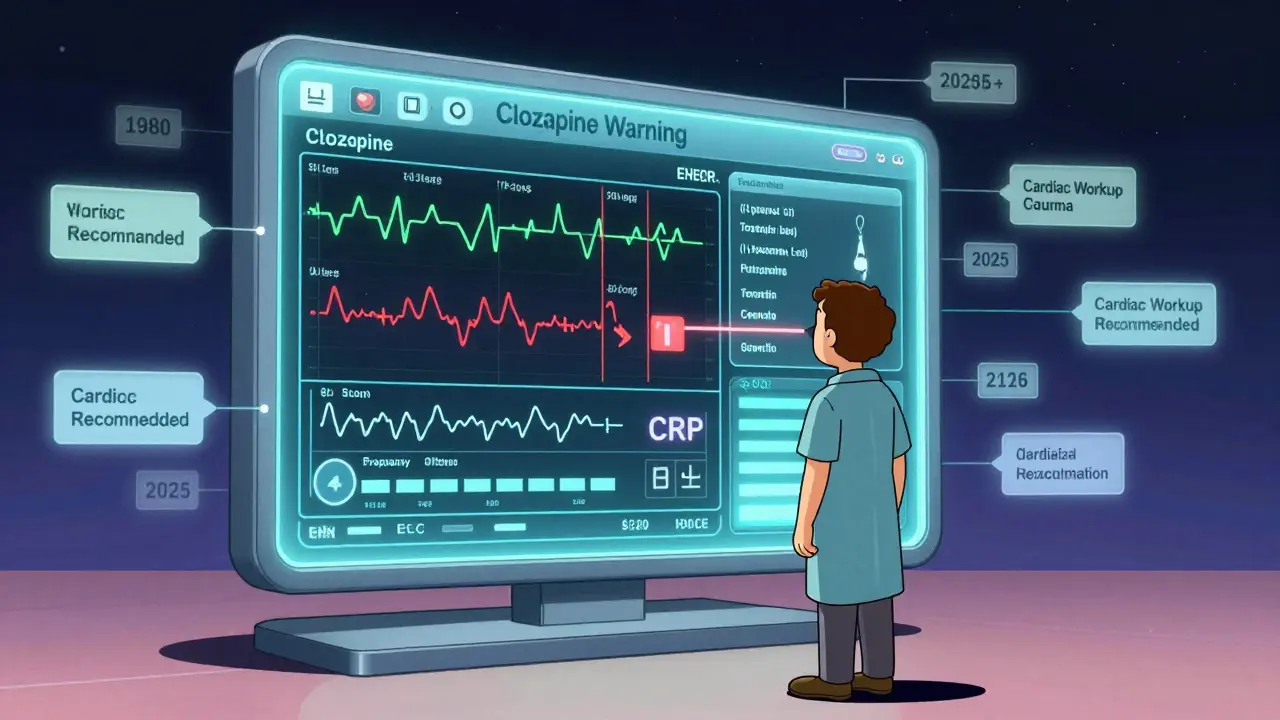

Boxed warnings aren’t magic. They only help if people see them and act on them. A 2017 study found only 43.6% of primary care doctors could correctly identify which drugs had boxed warnings during a clinic visit. On Reddit, physicians reported avoiding first-line antidepressants for teens not because the drug was ineffective-but because they feared the warning. And here’s the hard truth: not all warnings change prescribing habits. A 2021 study showed that only 61.2% of boxed warnings led to measurable changes in how drugs were prescribed. Warnings about rare but catastrophic events-like liver failure or agranulocytosis-had 78.4% compliance. Warnings about common side effects, like nausea or dizziness, had just 42.1% compliance. That’s why the FDA is testing "dynamic warning systems"-real-time alerts tied to electronic health records. Imagine a doctor clicks "prescribe clozapine," and the system pops up: "Mandatory cardiac monitoring required. Baseline EKG due within 72 hours. Next check-in in 7 days." That’s the future. The current system still relies on humans reading a PDF.

What You Should Do

If you’re a clinician:- Check the SrLC database quarterly-don’t wait for updates to land on your desk.

- Compare the old and new wording. Look for added populations, numbers, or monitoring rules.

- Don’t assume a warning is the same as it was five years ago.

- Ask your pharmacist: "Has this drug’s boxed warning changed recently?"

- Don’t panic if a warning is added. Ask: "What does this mean for me?"

- Know your monitoring schedule. If your drug requires blood tests or EKGs, write them down.

- Use Drugs@FDA to see the full label history.

- Look for the year the boxed warning was first issued and when it was last updated.

- Compare it to similar drugs. If one has a warning and another doesn’t, ask why.

The Bigger Picture

Boxed warnings are getting more frequent. In the early 2000s, the FDA issued 15-20 new ones per year. Now, it’s 25-30. Why? Because more drugs are approved faster-through accelerated pathways like Breakthrough Therapy. Between 2012 and 2022, 34.1% of drugs approved this way ended up with a boxed warning, compared to 22.7% of standard approvals. This isn’t a failure. It’s a sign that post-marketing surveillance is working. Drugs are getting approved based on smaller, shorter trials. Real-world use is the real test. And when problems show up, the system responds. But the system is strained. The median time from approval to a boxed warning has climbed from 7 years in 2002 to 11 years in 2009. That’s too long. The FDA’s 2023 Modernization Act 2.0 is pushing for real-world data to speed this up. By 2030, experts predict 40-45% of all marketed drugs will carry a boxed warning-up from 32% in 2020. The goal isn’t to scare people. It’s to make sure the right people get the right drug, with the right safeguards. A warning that says "avoid in patients with heart disease" is useless if the doctor doesn’t know the patient has heart disease. A warning that says "check EKG before starting and repeat weekly for 4 weeks" gives the doctor a clear action.Future of Boxed Warnings

The future isn’t bigger warnings. It’s smarter ones. The FDA is testing pilot programs that link drug labels to electronic health records. When a patient’s lab results or vitals meet certain thresholds, the system could auto-flag a warning or suggest a test. Imagine a patient on clozapine gets a fever. The EHR automatically checks the drug’s warning, pulls up the myocarditis criteria, and prompts the doctor: "Consider cardiac workup. Recommended: troponin, CRP, EKG." That’s the shift: from static text on a page to dynamic, data-driven safety. The warning isn’t just a box anymore. It’s part of a system. For now, you still need to read it. And you need to know how it’s changed.What does a boxed warning mean for my prescription?

A boxed warning means the drug carries a serious, potentially life-threatening risk. It doesn’t mean you can’t take it-it means you need to be monitored closely. Your doctor should explain what the warning means for you specifically: Are you in a high-risk group? Do you need blood tests or heart scans? Are there alternatives? Never stop a drug because of a warning without talking to your provider.

Can a boxed warning be removed?

Yes. If new data shows the risk is lower than previously thought-or if the original concern was misinterpreted-the FDA can remove or revise the warning. The most famous example is Chantix (varenicline). Its 2009 warning about depression and suicidal thoughts was removed in 2016 after a large clinical trial of over 8,000 people found no increased risk compared to placebo. The warning was taken off because the evidence no longer supported it.

Why do some drugs have boxed warnings and others don’t, even if they’re similar?

Because the risks aren’t the same. Two drugs might treat the same condition, but their chemical structure, metabolism, or how they interact with the body can lead to different safety profiles. For example, both clozapine and olanzapine are antipsychotics, but only clozapine carries a boxed warning for agranulocytosis because it causes severe drops in white blood cells at a much higher rate. The FDA evaluates each drug individually based on real-world data-not comparisons.

How often are boxed warnings updated?

There’s no fixed schedule. Updates happen when new safety data emerges. The FDA reviews reports continuously. On average, 15-20 boxed warning updates are issued each year. Some drugs get updated multiple times in a decade (like Clozaril), while others haven’t changed in 20 years. The Drug Safety-related Labeling Changes (SrLC) database tracks all updates since 2016 and is updated quarterly.

Are boxed warnings the same in other countries?

No. The U.S. FDA’s boxed warning is unique in its format and legal weight. Other countries use different systems: the European Medicines Agency uses "contraindications" and "warnings" in their summaries of product characteristics, but they don’t use a boxed format. Some countries have stronger warnings than the U.S., others weaker. A drug with a boxed warning in the U.S. might have no special alert in Canada, or vice versa. Always check the local prescribing information if you’re traveling or using foreign medications.

Keith Harris

February 5, 2026 AT 08:51Let me tell you something they don’t want you to know about boxed warnings-they’re not about safety, they’re about liability. The FDA doesn’t care if you live or die; they care if their name gets dragged through the mud when someone sues. That’s why they keep adding more numbers, more jargon, more ‘mandatory monitoring’-so when you die on clozapine, they’ve got 17 pages of documentation proving they warned you. It’s not medicine. It’s legal theater. And don’t even get me started on how they cherry-pick data to justify updates. The system’s rigged.

Kunal Kaushik

February 5, 2026 AT 12:37Wow, this was super helpful 😊 I never realized how much detail goes into these warnings. Thanks for breaking it down like this-makes me feel way more confident talking to my doctor now!

Caleb Sutton

February 7, 2026 AT 07:46They’re lying. Every single one of these warnings is a cover-up for pharma’s criminal negligence. The FDA is just a puppet of Big Pharma. They don’t update warnings because of data-they update them when the lawsuits get too loud. And the ‘dynamic EHR alerts’? That’s how they’ll track you. Next thing you know, your insulin dose gets auto-rejected because some algorithm says you’re ‘high risk.’ Wake up.

Katherine Urbahn

February 8, 2026 AT 17:25While I appreciate the thoroughness of this exposition, I must emphasize that the reliance upon the SrLC database, while commendable, is fundamentally insufficient. One cannot, in good conscience, entrust clinical decision-making to a quarterly-updated, publicly accessible repository that lacks real-time integration with EHRs. Moreover, the absence of standardized nomenclature across international regulatory bodies-such as the EMA’s ‘contraindications’ versus the FDA’s ‘boxed warning’-creates dangerous inconsistencies in global pharmacovigilance. This is not merely a communication issue; it is a systemic failure of translational safety.

Joseph Cooksey

February 9, 2026 AT 08:22You know, I’ve been in this game for 27 years-started when they still printed the black box warnings on paper inserts you had to flip through like a damn encyclopedia. Back then, we’d get one update a year, maybe two. Now? Every damn month, it’s something new. And you know what’s worse? The younger docs-they don’t even read the damn thing. They just Google it, see a Reddit thread, and think they’ve got it figured out. I’ve seen people miss a whole new contraindication because they didn’t compare the ‘previous text’ with the ‘revised text.’ You can’t just wing it. You’ve got to sit down, open the FDA archive, and trace the damn evolution. It’s not sexy. It’s not quick. But if you don’t, someone’s gonna die. And it’ll be on you.

Joy Johnston

February 9, 2026 AT 09:49This is such an important topic-and honestly, I’m so glad someone took the time to explain it clearly. As a pharmacist, I see patients panic when they see a boxed warning on their new script. The key is to help them understand it’s not a ‘don’t take this’ sign-it’s a ‘here’s exactly how to stay safe’ sign. I always say: ‘The warning isn’t there to scare you. It’s there to give you a roadmap.’ And if you’re ever unsure? Ask. Always ask. Your life matters more than your pride.

Shelby Price

February 9, 2026 AT 22:48Interesting. I never thought about how the language changed from ‘may cause’ to actual numbers. Makes me wonder-do the numbers ever get revised downward? Or is it always ‘add more scary stuff’?

Jesse Naidoo

February 10, 2026 AT 14:44So… if the FDA updates a warning, does that mean everyone who took the drug before the update is now at risk? Like, am I permanently damaged because I took this before the cardiac monitoring requirement? Or is it just future patients? I need to know. I need to know NOW.

Zachary French

February 11, 2026 AT 22:11Look, I’ve been reading these warnings for a decade. And I’ll tell you flat out: the FDA doesn’t update these because they care about you. They update them because the lawyers told them to. The numbers? Fake. The ‘1 in 500’? That’s based on 300 people in a trial. The ‘mandatory EKGs’? Half the clinics can’t even do them on time. And the ‘dynamic alerts’? That’s just a fancy word for surveillance. They’re not making us safer-they’re making us compliant. And don’t even get me started on how they remove warnings… like Chantix. That was a cover-up. The trial was funded by Pfizer. You think they’d remove a warning if the data was real? Please.

Daz Leonheart

February 13, 2026 AT 11:29You got this. Seriously. I know it feels overwhelming, but you’re already ahead just by asking questions. Every time you check the label, every time you ask your pharmacist, you’re doing something most people never even think about. Keep going. You’re not just protecting yourself-you’re protecting your whole family. One step at a time.

Amit Jain

February 14, 2026 AT 21:43Simple truth: boxed warning means check with doctor. Not scary. Not confusing. Just: talk to someone who knows. No need for databases. Just ask.

Alec Stewart Stewart

February 15, 2026 AT 22:06This is such a good breakdown. I’m a nurse and I’ve seen so many patients scared off by these warnings. But once we sit down and go through what it actually means-like, ‘This doesn’t mean don’t take it, it means we’ll check your heart every week for a month’-they breathe again. We need more of this. Not just for docs. For everyone.

Demetria Morris

February 16, 2026 AT 21:49It’s unconscionable that we allow pharmaceutical companies to influence safety labeling through post-marketing data that is, by its very nature, uncontrolled and biased. The FDA’s reliance on MedWatch reports-many of which are submitted by patients with no medical training-is a grotesque abdication of scientific responsibility. The fact that these warnings are now being ‘optimized’ for EHR integration suggests a terrifying prioritization of automation over clinical judgment. This is not progress. It is surrender.

Susheel Sharma

February 18, 2026 AT 01:30Interesting. But let’s be real-the real issue isn’t the warning. It’s the cost of compliance. Who’s paying for weekly EKGs? Who’s covering the time off work? Who’s monitoring the patient who can’t afford the follow-up? The FDA gives the warning. The system ignores the cost. And the patient? They just stop taking the drug. And then they die of the disease. The warning didn’t save them. The bureaucracy did.

Janice Williams

February 18, 2026 AT 04:14Let me just say this: if you’re a doctor who prescribes a drug with a boxed warning without reading the full history of its revisions, you are not a healer-you are a liability waiting to happen. And if you’re a patient who doesn’t demand to see the changes, you are complicit in your own risk. This isn’t about fear. It’s about accountability. And if you’re not holding yourself or your provider to this standard, you’re not just ignorant-you’re dangerous.