Pheochromocytoma: What It Is, How It Causes High Blood Pressure, and Why Surgery Is Often the Cure

Imagine your body suddenly flooding with adrenaline-heart racing, hands sweating, head pounding-while you’re sitting quietly at your desk. No stress. No exercise. Just a silent tumor in your adrenal gland firing off hormones like a broken alarm clock. That’s pheochromocytoma-a rare but dangerous adrenal tumor that tricks your body into thinking it’s in constant danger.

What Exactly Is a Pheochromocytoma?

A pheochromocytoma is a tumor that grows in the adrenal medulla, the inner part of your adrenal glands. These glands sit on top of your kidneys and normally help control stress responses by releasing hormones like epinephrine and norepinephrine. But when a tumor forms there, it doesn’t turn off. It keeps pumping out these hormones, even when you’re asleep or relaxed.

It’s not cancer in most cases-about 90% are benign. But even benign tumors can be life-threatening because of how they mess with your blood pressure. These tumors are rare: only 0.1% to 0.6% of people with high blood pressure have one. Still, they’re one of the few causes of hypertension that can be completely cured with surgery.

What makes pheochromocytoma tricky is that it often looks like something else. Panic attacks, migraines, or even menopause can mimic its symptoms. That’s why many people go years without a diagnosis. The average delay? Over three years. And nearly a quarter of patients are first told they have an anxiety disorder.

How Does It Cause High Blood Pressure?

High blood pressure from pheochromocytoma isn’t steady like typical hypertension. It comes in sudden, violent spikes-sometimes hitting 200/120 mmHg or higher. These spikes happen without warning and can last minutes to hours. Afterward, your blood pressure might drop so low you feel dizzy or faint.

The reason? Catecholamines. These are the same chemicals your body releases when you’re scared or running from danger. But with a pheochromocytoma, they’re released randomly. A bump in the car, a loud noise, even urinating (if the tumor is in the bladder) can trigger a surge. That’s why some people have spells during exercise, stress, or even anesthesia.

Three symptoms show up in most cases: severe headaches (85-90% of patients), drenching sweats (75-80%), and a pounding heartbeat (70-75%). You might also feel pale, nauseous, anxious, or lose weight without trying. Some patients describe it as a “storm” inside their chest that comes and goes.

Unlike essential hypertension-which affects nearly half of U.S. adults and creeps up slowly-pheochromocytoma’s spikes are dramatic, unpredictable, and tied to that classic trio of symptoms. If your blood pressure jumps randomly and you have those other signs, this should be on the doctor’s radar.

How Is It Diagnosed?

Doctors don’t start with imaging. They start with blood and urine tests. The gold standard is measuring fractionated metanephrines-the breakdown products of epinephrine and norepinephrine-in a 24-hour urine sample or a plasma test. These tests are over 95% sensitive. If levels are three times above normal, the chance of a pheochromocytoma is very high.

Why not just do a CT scan first? Because many people have harmless adrenal bumps that show up on scans. If you test positive for high metanephrines, then you get imaging-usually a CT or MRI-to locate the tumor. Newer scans like 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT are even better at finding small or hidden tumors, especially if they’re outside the adrenal gland (called paragangliomas).

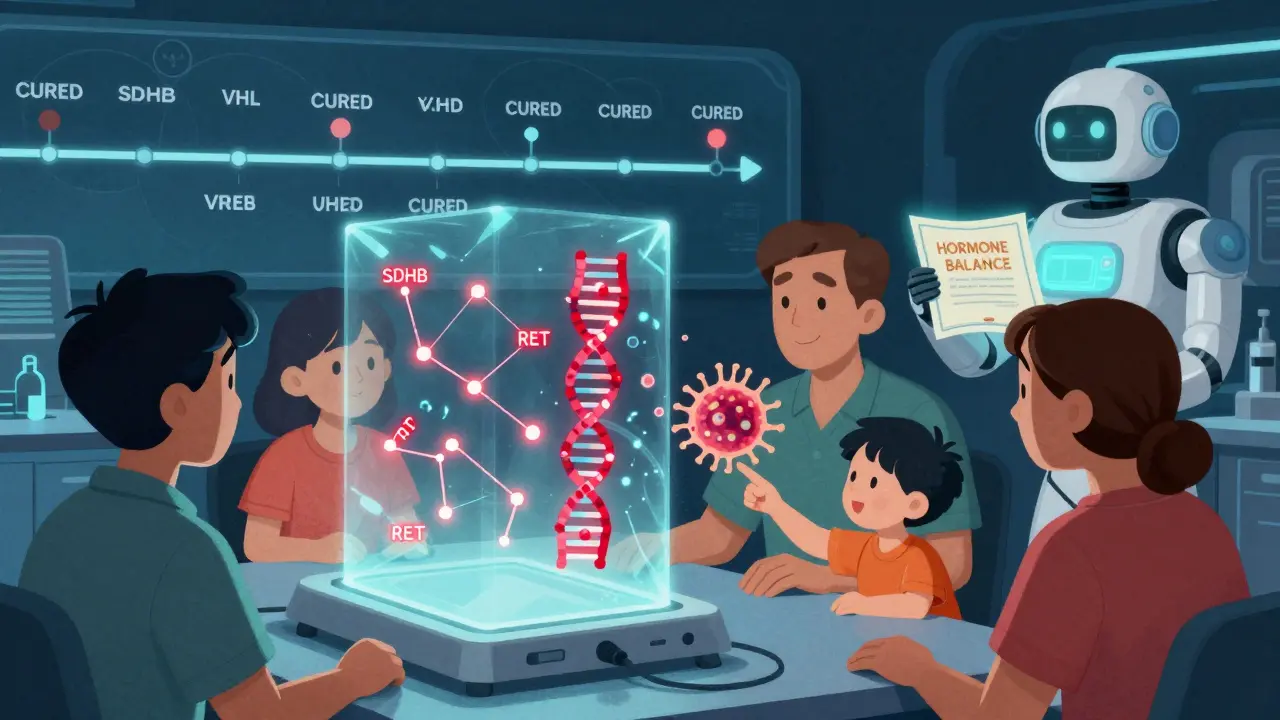

Genetic testing is now recommended for everyone diagnosed with pheochromocytoma. Why? About 35-40% of cases are linked to inherited gene mutations-like SDHB, SDHD, VHL, or RET. These mutations don’t just affect you; they can affect your children, siblings, or parents. Finding one means your whole family may need screening.

Why Surgery Is the Only Real Cure

Here’s the good news: if you catch it early, surgery can cure you. After removing the tumor, 85-90% of patients no longer need blood pressure meds. Their blood pressure returns to normal within days or weeks.

But surgery isn’t simple. You can’t just go in and cut it out. The tumor is packed with hormones. If you touch it before blocking those hormones, you risk a catastrophic surge-blood pressure shooting up, heart racing out of control, even death. That’s why preoperative preparation is non-negotiable.

For 7-14 days before surgery, patients take alpha-blockers like phenoxybenzamine. These drugs block the effects of excess adrenaline. Doctors also push fluids and salt to expand blood volume-because these tumors cause chronic blood vessel tightening, which shrinks your total blood volume by 20-30%. Skipping this step is dangerous.

The surgery itself is usually done laparoscopically-small incisions, camera, minimal recovery. At top centers, over 85% of unilateral cases are done this way. But if the tumor is large, stuck to nearby organs, or there’s bleeding, surgeons may need to switch to open surgery. Recovery is quick for most: 1-2 days in the hospital, back to work in two weeks.

What Happens After Surgery?

Most people feel better fast. One patient on a support forum wrote: “My blood pressure normalized within 48 hours. Off all meds in three weeks.” That’s the dream.

But not everyone has a smooth recovery. If both adrenal glands are removed-which happens in rare cases like bilateral tumors or genetic syndromes-you’ll need lifelong steroid replacement: hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone. Without them, your body can’t handle stress, and you risk adrenal crisis-a medical emergency.

Some people deal with long-term fatigue for months after surgery. About 12% report chronic tiredness lasting six months or longer. It’s not fully understood why, but it’s real. And if you have a genetic mutation like SDHB, you need annual whole-body MRIs for life. These tumors can come back or spread, even if they were “benign” at first.

What Happens If It’s Missed or Ignored?

Left untreated, pheochromocytoma can kill you-not slowly, but suddenly. A single hypertensive crisis during surgery, childbirth, or even a routine doctor’s visit can trigger a heart attack, stroke, or organ failure. That’s why doctors say: Test before you cut.

And if you’re diagnosed but refuse surgery? Your risk of death over 10 years jumps dramatically. Benign tumors that aren’t removed still carry a 10-20% chance of becoming malignant over time. And malignant pheochromocytomas are tough to treat. Survival drops to about 50% at five years.

That’s why early detection matters. If you’ve had unexplained high blood pressure spikes, sweating, and headaches-especially if it runs in your family-push for metanephrine testing. Don’t settle for “it’s just anxiety.”

What’s New in Treatment?

Research is moving fast. For metastatic cases-where the cancer has spread-new therapies are showing promise. Peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT) using 177Lu-DOTATATE has helped 65% of patients in early trials. It targets tumor cells with radiation while sparing healthy tissue.

Another exciting development is Belzutifan, a drug approved for VHL-related tumors. It blocks a protein (HIF-2α) that tumors use to grow. Early results show it can shrink tumors without surgery in some cases.

And scientists are working on liquid biopsies-blood tests that could one day detect pheochromocytoma before symptoms even start. That’s still experimental, but it could change everything for families with known genetic risks.

Final Thoughts

Pheochromocytoma is rare, but it’s one of the few medical conditions that can be completely cured. The problem isn’t treatment-it’s recognition. Too many people suffer for years because their symptoms don’t fit the mold of “typical” high blood pressure.

If you’ve had unexplained spikes in blood pressure, sweating, and headaches, ask your doctor about metanephrine testing. Don’t wait. Don’t assume it’s stress. And if you have a family history of adrenal tumors, cancer, or neurological disorders, get genetic counseling.

This isn’t just about managing a disease. It’s about finding the hidden cause-and fixing it before it fixes you.

Can pheochromocytoma be cured without surgery?

No, surgery is the only cure for pheochromocytoma. Medications can control symptoms and lower blood pressure, but they don’t remove the tumor. Without removal, the tumor keeps releasing hormones, and the risk of sudden, life-threatening spikes remains. Even in cases where the tumor is too risky to remove, surgery is still the goal-unless the cancer has spread too far.

Is pheochromocytoma hereditary?

Yes, about 35-40% of cases are linked to inherited gene mutations. Common genes include SDHB, SDHD, VHL, RET, and NF1. Even if no one in your family has had it, you could still carry a mutation. That’s why genetic testing is now recommended for every patient diagnosed with pheochromocytoma. If you test positive, your close relatives should be screened too.

Can pheochromocytoma come back after surgery?

Yes, especially if you have a genetic mutation like SDHB. For those with sporadic (non-hereditary) tumors, recurrence is rare-under 5%. But for hereditary cases, recurrence rates can be 10-20% over 10 years. That’s why lifelong follow-up is needed. Annual imaging and hormone tests help catch any new tumors early.

What happens if you have both adrenal glands removed?

If both adrenal glands are removed, your body can no longer produce cortisol or aldosterone. You’ll need lifelong hormone replacement: hydrocortisone (15-25 mg/day) to replace cortisol and fludrocortisone (0.05-0.2 mg/day) to replace aldosterone. Missing doses can lead to adrenal crisis-low blood pressure, vomiting, confusion, and even death. Patients must carry an emergency injection of hydrocortisone and wear a medical alert bracelet.

How do you know if your high blood pressure is from pheochromocytoma?

Look for the classic triad: sudden, severe headaches; drenching sweats; and a racing or pounding heartbeat-especially if these happen in episodes. Blood pressure spikes above 180/110 without warning, often triggered by stress, exercise, or urination. If you’ve been told you have essential hypertension but meds aren’t working, or you have unexplained weight loss or anxiety, ask for a plasma or urine metanephrine test. It’s the only way to rule this out.

Ben Kono

January 13, 2026 AT 00:32Rinky Tandon

January 13, 2026 AT 22:01Daniel Pate

January 14, 2026 AT 05:08TiM Vince

January 14, 2026 AT 22:57gary ysturiz

January 16, 2026 AT 12:26Jessica Bnouzalim

January 18, 2026 AT 06:39laura manning

January 18, 2026 AT 07:34Bryan Wolfe

January 18, 2026 AT 08:34Sumit Sharma

January 18, 2026 AT 21:25beth cordell

January 19, 2026 AT 21:35Lauren Warner

January 20, 2026 AT 22:29